A relatively small number of Jews, 3,500–4,000, found refuge in Ecuador through 1942. Settlement projects from the mid-1930s, including the plan for long-term settlement of 50,000 families in mostly remote areas, were supported neither by the Ecuadorian public nor by the Jewish settlers and proved to be untrustworthy and impractical. For most of the Jews who found refuge in the country until 1942, Ecuador, with its three million inhabitants, was a second-choice place of exile, since they had failed to find asylum in another, preferred country. The majority came from Germany and Austria after the pogrom of November 1938 (*Kristallnacht) having lost hope that they could stay in their native country. Part of them settled in Guayaquil, the biggest city of the country, which was a real trading center with a population of about 180,000.

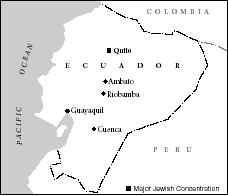

Major Jewish communities in Ecuador.

Located near the Pacific coast, it had a tropical climate. The vast majority, however, preferred the capital, Quito, situated in the Andes at an altitude of 9,200 ft. (2,800 m.). Few settled in small towns like Ambato (100), Banos, Cuenca (30), and Riobamba, or in the jungle around Puyo.

In Quito as in Guayaquil they were concentrated in several streets in the city center or not far from it. Quito with 150,000 inhabitants had no industry and only one multi-story building. Compared to middle-class European standards the living conditions were cramped and primitive, with no infrastructure and with infectious diseases and a lack of hygiene threatening their health. Many of the immigrants had only meager financial means, though many of them had brought their household goods and other possessions. Since the authorities returned the deposits that the immigrants had made to receive their visas (a few hundred dollars each), most of them had money to invest. Many had to earn their livings in unfamiliar occupations. But wherever it was possible they tried to continue in their former professions or similar ones.

Despite the regulations restricting immigration to industrial or agricultural laborers, only a minority worked in agriculture. Because of the difficult living and working conditions and their lack of knowledge such onerous attempts were given up. The project of HICEM and the Joint in 1937 to settle 60 families in the area of Ambato for chicken farming was among those failed attempts. A considerable number of the immigrants were active in trade, as peddlers, in retail and wholesale, and in the import and export trade. While the majority of the enterprises in the first years required hard work by all family members to reach a subsistence level, some of the enterprises reached a considerable size by 1942 and exist until today. The most successful were those that found a niche in the market, offering services and goods unknown in the country or absent from the market because of the war. In the field of food and textile production, in the metallurgical (El Arco, Ideal, Siderúrgica SA.) and pharmaceutical industries, in services and the hotel trade, they played an important role and brought a dynamic element into business life. Names like Rothschild, Seligmann, Neustätter, Di Capua, and Ottolenghi stand out.

The fact that the authorities as a rule did not enforce industrial or agricultural employment made it easier for the immigrants to integrate into the economic process but soon led to anti-Jewish pressure on the part of the local population. While the presidents José Maria Velasco Ibarra (1934–35, 1944–47) and Carlos Arroyo del Rio (1940–44) approved the immigration of Jews, some circles espoused an antisemitic line with recourse to the German-based press and deep-seated Christian prejudices. Also textile merchants of Arab origin, especially from Lebanon, who had lived in Ecuador for decades, considered the Jews undesirable competitors. In August 1944 Velasco Ibarra rescinded the regulations that restricted immigration to industrial or agricultural employment, but already at the end of the 1940s the authorities stepped up the control of Jewish enterprises and in 1952 another law was passed requiring proof that a foreigner was engaged in the occupation stipulated in his entry visa. This legislation was counteracted by the intervention of the World Jewish Congress. Within these limited political and social limitations the immigrants were free to do whatever they wished. There was no bar to practicing their religion or founding associations.

The biggest group among the refugees was in Quito. Its nucleus was the above-mentioned HICEM Committee founded in 1938. In the same year the Asociación de Beneficencia Israelita was founded, reaching its peak with over 540 members (heads of families) in 1945. Unlike most Latin American countries, where Jewish communities already existed and the newcomers founded their own separate organizations according to their countries of origin, the "Beneficencia" united Jews from Germany, Austria, Italy, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, the Soviet Union, and the Baltic states.

Though there was some religiously motivated separation this was of minor significance. While in Guayaquil differences of opinion about Zionism were a greater potential cause of discord than in Quito, in religious matters the situation was quite the opposite. In Guayaquil the strongest organization, Comunidad de Culto, with more than 140 members, combined the Sociedad de Beneficencia, founded in 1939–40, and the Centro Israelita, which had split off in 1944, both competing for cultural primacy. Under the impression of the foundation of the State of Israel all organizations in Quito united under the umbrella of the "Beneficencia" while in Guayaquil it took almost 20 years more to reach such unity.

The "Beneficencia" did a great deal to create a center of religious, social, and cultural life for its members. A bulletin called Informaciones para los Inmigrantes Israelitas, in the first period mainly written in German, informed readers about the community, the host country, and international affairs. Based on the model of their European countries a court of arbitration, a ḥevra kaddisha, a women's association, a cooperative bank, Maccabi, and B'nai B'rith were established. In Quito and in Guayaquil Zionist organizations were founded that succeeded in winning the support of public figures in the host country for the objectives of Zionism. The Ecuadorian representative cast his vote in the UN General Assembly resolution of November 29, 1947, in favor of the partition of Palestine. Ecuador and Israel established diplomatic relations. From the late 1960s a network of technical cooperation and assistance was developed between the two countries, especially in the fields of agriculture, water development, youth training, and technology.

Jews achieved prominence in Ecuadorian society beyond the economic field. They contributed to cultural development in music, painting, theater, arts and crafts, architecture, literature, science, journalism, and publishing.

As the majority of the immigrants had regarded their stay in Ecuador as a temporary episode, emigration after the end of the war was considerable. By 1948 about half the Jews in Quito had emigrated, mainly to the U.S. On the other hand, a considerable number of survivors of the Holocaust arrived in the early postwar years. Because of continuous emigration, mortality, and partial assimilation of the following generation, which considered Spanish its mother tongue, the immigrant organizations lost their pivotal role as preservers of social and cultural identity. However, the Jews continued to form a small middle-class group largely cut off from the strong Catholic upper class and the masses of mestizos and the indigenous population.

No comments:

Post a Comment